One modern classroom skill is global awareness. Our third graders have been taking advantage of many “Skypportunities” across the globe over the last few months. So when considering a research project for 3rd grade, I thought it only befitting to do country studies with the students.

Introduction

After each student had chosen a country to study, they brainstormed specific information they wanted to learn about the country. We then collected the information in a KW chart.

I then used the KW chart to create a Note Taking Graphic Organizer for the students. I used all of the students’ questions and added three of my own:

- Identify one way this country is different from ours

- Identify one way this country is the same as ours

- Would you like to visit the country some day? Why or why not?

Research

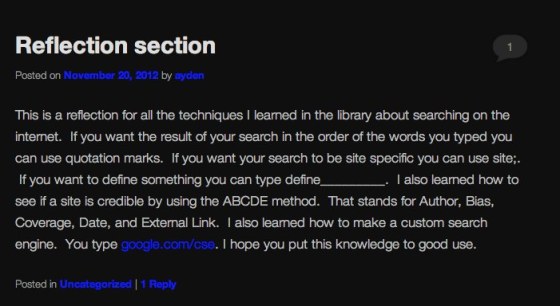

For their information resource, students searched the Kids Infobits (Gale) database. Since they had been introduced to the database earlier, students knew how to navigate this information resource. We spent four 45-minute sessions finding information, reading text for information, and summarizing information using the note taking organizer. I like the Kids InfoBits database as it exposes students to different types of source materials (reference, magazine and newspaper articles, maps, graphs and charts, images). The students quickly figured out that a lot of the information they needed could be found in one of the “Country Overview” reference articles. One student discovered that there are pie charts in the “Graphs and Charts” section showing a country’s religions, which nicely complemented their math lessons where they were learning all about such graphic representations.

Product

For a product, students created a Top Five Reasons to Visit/Live report (see “Foundations for Independent Thinking: Look to Bloom and Marzano” by Liz Allen) using Tech4Learning’s Pixie software. The project required not only a transfer of information collected on the organizer to Pixie, but students were challenged to provide detail and/or comparisons in their statements. For example, rather than simply writing: “They have lots of different religions”, a more specific statement would be, “Judaism is the major religion in Israel.” Or, rather than stating that “They have interesting places to visit”, “In China, you can visit the Great Wall, which is so big that you can see it from space.”

After all their hard work, students shared their products with the class. There were lots of questions for each presenter from curious classmates!

Negotiating Information Overload

To some degree, this was very much a student-driven project, as students chose a country to research and generated research questions about the country of their choice. The level of engagement was high throughout the project. Students really enjoyed finding out about unique animals and special foods and loved to share the information with their classmates as they were discovering new information during the research process.

Still, reading text for information clearly is challenging for all students. And even though we used a kid-friendly database for our information resource, not all information was easily understood. Students were challenged to learn new vocabulary (e.g., population, climate, transportation, reference source) and needed many reminders to not simply scan an article but to read it in its entirety. I limited the research stage to four sessions. Some students had already completed their organizers after three sessions, others were not finished after four–but all students had enough information to create their products.

Creating the Top Five Reasons report again challenged them to think critically by using the information they had gathered, evaluate it, and then apply it in a new way. Initially, we required the Top Ten reasons, but found that most students simply listed very basic information (as mentioned above). So we changed the requirement to the Top Five insisting on quality statements: Convince me to want to visit or even live in the country.

I think students found this last step so challenging because while they had gathered a lot of information, they often did not read texts in their entirety but rather skimmed or scanned them for the information sought and then moved on. I’ve observed this research behavior in many of my older students as well: Skim or scan the first few results of a Web search, then enter a new search or simply give up.

Not reading closely also caused some students to provide incorrect information. For example, one student claimed that the South Korean currency is the “Korean dollar” and another student claimed that Boxing Day is celebrated by Kangaroos boxing each other! While very imaginative, the information obviously is incorrect.

If I were to do this project again, I would begin by modeling the information gathering process with a focus on how to closely read and extract information. Also, I would focus the information sought on more unique facts and encourage students not to get overwhelmed. So rather than determining the political system or size of the country (neither of which really tell the students much anyway), focus on customs and culture. Some such questions were included in the graphic organizer, but they were not the focus of the research. I believe fewer but more in-depth questions would have forced the students to read text more closely and made it less challenging to come up with those reasons that can convince me to live or move to another country!